Reading the Manual

Most searching today generally involves a search engine of some sort. Search engines (e.g. Google) are extremely complex. Fortunately, most of them have a simple mode where anybody can just just enter some words into a box and press Search. It works fine for finding many things and is also very useful in early stages of research.

But what about when lives depend on the results of your research (or even your grade)? You need to know how to dial it up a notch. You need to go beyond the dummy mode that most search engines default to. But how?

Almost Universal Search Operators

A search operator is some special text that modifies your search by operating on all or some of your search terms. Even though many of these operators are common to different search engines, they may have implemented them slightly differently or used different syntax. Here is a list of three types of search operators that should be present in any good search engine:

-

- Boolean Operators

- Wildcard Symbols

- Scope/Location/Proximity Operators

Boolean Operators

AND - search for items with all your search terms

OR - search for items with either of search terms

NOT - ignore results with these terms present (the minus sign is used for NOT by Google and other search engines)

Boolean Operator Examples

asphalt OR bituminous AND pavement OR paving AND road OR "highway construction" -roof -roofing

"GIS" OR "Geographic Information System"

Wildcard Symbols

Symbols that can stand for unknown letters or multiple prefixes or suffixes.

Usually a question mark (?) is used for single letters and an asterix (*) is used for truncation or multiple words.

Wildcard Examples

"Jens?n" as a search term will return "Jensen" and "Jenson"

"stom*" as a search term will return "stomp", "stomping", "stomach", "stoma", etc...

Scope/Location/Proximity Operators

There are many other operators in the form of symbols, characters, words or even boxes & switches that modify the way a search is conducted. These may limit the scope of the search to particular time frame, particular locations (physical or virtual) or types of results (e.g. books or articles) or even filetypes (e.g. PDF or PowerPoint files). They may tell the search engine to only look at words in certain parts of the documents being search (e.g. title, abstract, URL, etc.). Finally they may be used to control the proximity of search terms to each other beyond direct quotes, e.g. near operators.

These types of operators are varied and often unique to the search platform being used. This is why it is important to always read the manual so you know what works on that platform. What works at Google Scholar may or may not work at SCOPUS or Web of Science.

Examples

Limit Google results to institutions with an Educational (.edu) top level domain name:

asphalt OR cement durability site:.edu to your search

Limit Google results to only PowerPoint files:

"road construction" filetype:pptx

Specify where your search terms should occur. Many of the specialized collections of articles subscribed to by the library (Databases) use (TI) to look for your terms in the Title, or (AB) to look in the abstract. Google has similar functionality by adding allintitle: or allinURL: to the front of your query. If you only need a single search term in the title of a webpage use intitle:searchterm instead.

(Google Scholar example) intitle:road intitle:construction asphalt durability

(COMPENDEX key words example) (((road construction) WN TI) AND ((asphalt durability) WN ALL))

One of the best ways to learn the basic syntax is to use the advanced search boxes and then look at the syntax at the top of your results list. If you find yourself working in a particular search engine more than a few times or are having trouble narrowing things down, look for the Help button and read up on the rules.

The next tab: Finding & Using The Correct Words

Finding the Right Words

- Start with what you know and keep track of new words as you find them.

- Find new words by talking to an expert (your professor, your employer, etc.), in articles (scholarly, online, Wikipedia, Encyclopedias, News, etc.),and books. Don't forget to use your thesaurus or dictionary - particularly subject specific dictionaries (online & in print).

- Use your new words to perform further searching. Add them as additional terms (using the Boolean Operator OR) or in place of previous terms.

- The “right words” won’t necessarily be right everyplace. A word that successfully returns many results in Google may not return anything in Google Scholar. Scholarly literature is generally more formal than writing on the web. When using scholarly databases of article citations, the articles are usually tagged with "controlled vocabulary" - the commonly accepted words in a discipline. In engineering fields there may be a classification code in addition to, or instead of, a controlled vocabulary. Note these standardized terms along with the uncontrolled keywords provided by authors or even tags by other visitors.

- Re-search. Searching Google (or other Internet search engines like Bing or Yahoo) is like going shopping at Costco. They have a lot of stuff and you can probably find something that works if your need isn't too specialized. The more specific your need, the more likely you are to go to a specialty store. There are specialty search engines for various topics or even file formats Try different combinations of your words with different operators to limit where those words occur and/or where you results are coming from.

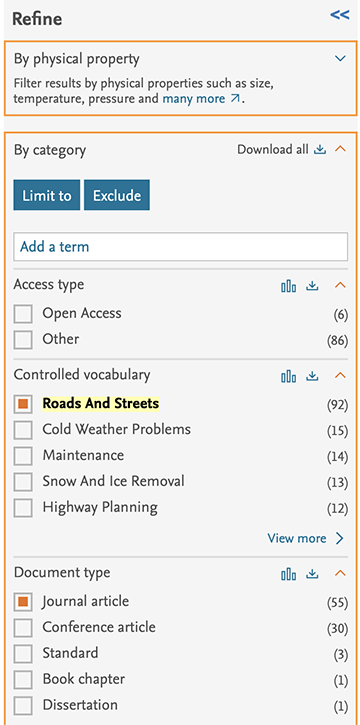

Most scholarly databases will have a way to browse through their controlled vocabulary, allowing you to include it in your search, like this example looking for the keywords asphalt and durability in any field of papers that have been assigned with the controlled vocabulary ROADS AND STREETS.

Copy and paste (({ROADS AND STREETS} WN CV) AND ((COLD WEATHER) WN ALL)) into COMPENDEX Search form to see an example. Most databases don't require you to know their syntax to get results. In this case, you could also start by typing cold weather into the Quick Search form, then selecting Roads And Streets from the controlled vocabulary list and Journal Article from the Document Type list to refine your results. Search then Refine is the way most academic databases work, allowing you to start broad and remove or add based on additional criteria

The Next Tab: Searching The Correct Places

Re-Search

A general rule for searching is to start broad and progressively narrow your search until you find what you want. When searching online, start with a general search engine or database such as Google Scholar (or even vanilla Google), or Ebsco's Academic Search Ultimate. Whether any of Google's offerings or a multi-disciplinary academic database like EBSCOHOST's Academic Search Ultimate are good enough for your purposes depends not just on the topic of your research, but how "serious" it is as well. It is possible to get absolutely correct information about many things from Google. Use search engines like these to discover the best search terms and refine your topic. Then take those search terms to discipline specific subscription databases (e.g. ASCE Research Library)If your research topic is highly specific, sensitive, or the subject of speculation you may need to go to sources that are not on the open Internet and are more specialized that "academic search".

What HBLL Database do I Use?

The HBLL website can be confusing when trying to determine where to search. This is because it attempts to provide access to hundreds of databases from various companies as well as individual journal subscriptions and the physical collections in the library.

Searching all these databases at once, then sorting them in a useful manner is not practical. The HBLL search box provides results from several broad coverage databases in addition to the physical holdings of the library. Unfortunately, this often results in a "jack of all trades, master of none" situation. In most situations you will get better results searching individual databases covering your area of interest. The content is less cluttered with things you don't want. For example, you won't find poetry that mentions rivers or buildings in the American Society of Civil Engineers Research Library). Additionally, each database often has custom search tools and methods which allow you to be more detailed in your searches. So, how should you use the library web page to find what you are looking for?

Let's take a look. I've highlighted the main areas of the HBLL webpage that will be useful to you when doing research.